Nutmeg's introduction to inflation and interest rates, how they are linked and what they mean for investors. This is a handy resource to help you see today's trends in context.

At a glance:

- Inflation is the increase in the cost of goods and services over time.

- Inflation affects the value of any interest on savings or investing gains you make with your capital.

- The Bank of England (BoE) has a set target of 2% inflation in the UK, and if it goes much higher than this it can be detrimental to the economy. One tool in the BoE's armoury is to raise interest rates to slow the rate of price rises.

- Interest rates affect how much companies and consumers are willing to borrow. As rates go up, borrowing becomes more expensive, and so it encourages saving instead.

- Stocks and shares can be impacted by rising inflation, as higher prices of goods and services can hurt consumer spending.

- Changes in interest rates also affect the price of bonds – they have an inverse relationship in that when interest rates go up, the price of most existing bonds will tend to fall, and vice versa when rates go down.

- Professional investors, such as portfolio managers, watch the relationship between inflation and interest rates, which can inform their trades and investment opportunities.

What is inflation?

Inflation is the increase in the cost of goods and services over time. Each month in the UK, the Office for National Statistics measures the prices of a selection of roughly 700 goods and services – from a pint of milk to major purchases such as a holiday.

The percentage change in this Consumer Price Index (CPI) compared to the same period the year before defines the official rate of inflation. For example, if inflation is at 5%, something that cost £1 last year might now cost £1.05p.

What causes inflation?

There are three broad causes of inflation, which we’ll outline here:

- Demand-pull inflation: This is when the prices of goods and services increase when the demand for them exceeds the supply. This is usually associated with a strong economy – as it strengthens, employment tends to rise. As employment rises, more people have money to spend so demand for goods and services increases. An example is the long-term trend of house price rises in big cities, such as London, where space is at a premium and there’s not enough new properties being built to satisfy growing demand to live there.

- Cost-push inflation: This is when the supply of goods or services is limited in some way but demand remains the same, pushing up prices. Cost-push inflation is sometimes associated with an unexpected event that disrupts supply. For example, the outbreak of conflict in Ukraine aggravated a steep rise in energy prices early in 2022 as worries intensified about disruption in supply of oil and gas from the region.

- Built-in inflation: As demand-pull and cost-push inflation persist, businesses and consumers may assume this will continue forever. Companies, expecting demand to continue to outweigh supply, and the costs in their supply chain to creep up, will continue to increase the price of their goods and services to maintain profit margins. It's no surprise then that employees continue to ask for pay rises to meet expected cost increases. While companies might resist this in tougher times, eventually they have to oblige to attract and keep the best workers.

Inflation is rarely explained by a single factor. All three of the above types of inflation may be happening in an economy at the same time – or may be affecting different sectors to varying degrees.

Is inflation always a 'bad' thing?

No, a little inflation is a good thing for the economy. It helps borrowers, including the Government, because it erodes the value of their debt over time.

If wages increase with inflation, and if the borrower already owed money before the inflation occurred, the inflation could benefit the borrower (all other things, including any interest payable, remaining unchanged)

This is because the borrower still owes the same amount of money, but now they may have more money in their pay to settle the debt.

This in turn can stimulate borrowing, investment in the economy and economic growth, and makes public finances easier to manage.

Central banks in the UK, Europe, and the US tend to target a 2% or 2.5% rate of inflation, which is seen as a healthy range for a growing economy.

If inflation is too high, or too unpredictable, this can make decision making more difficult for individuals, companies, governments, and the economy more broadly. Savings lose their value - most accounts offered by banks carry a lower rate of interest than inflation - businesses struggle to plan, and higher costs of living can mean consumers tighten their belts.

If inflation is close to zero, or negative (deflation), this is also a problem that can lead to high unemployment and economic recession. The 'sweet spot' for policy makers is to have manageable low levels of price rises, like the 2% or 2.5% we outlined above.

UK inflation in context

At the height of the economic crisis in 1975, UK annual inflation peaked at 24.5%, following two major oil shocks. At the other end of the scale, in 2015, as austerity measures stifled UK demand, it touched a low of -0.1%.

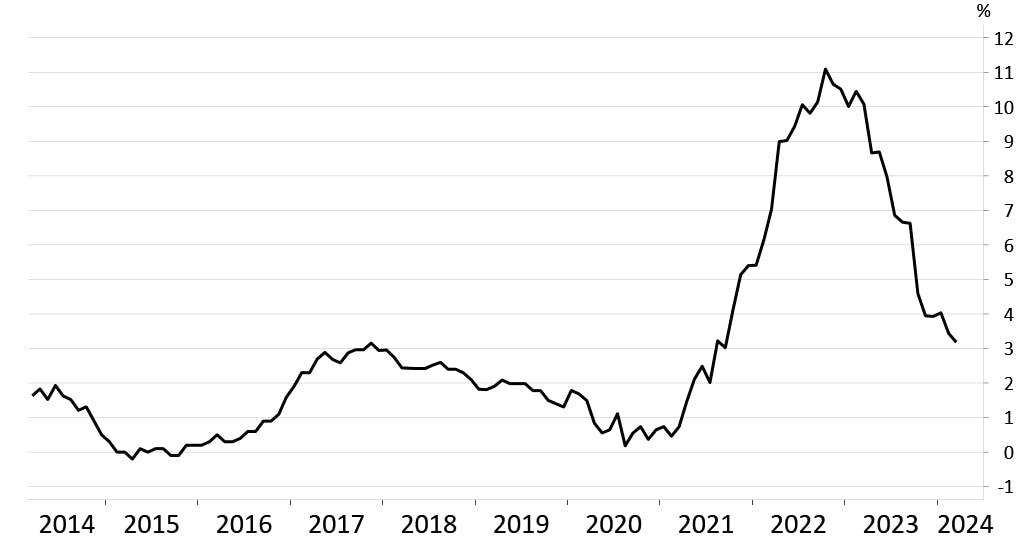

More recently, inflation reached a 40 year-peak of 11.1% in October 2022. This was driven by the delayed effects of pandemic lockdowns, and the impact Russia's war in Ukraine had on energy prices.

Between these extremes, inflation has typically ranged between 2% and 5%.

UK inflation (YoY) 10 years

Source: ONS, Macrobond

Historical periods of high inflation

Major inflation events are often remembered as having been caused by a particular event – but it's often more complicated.

- 1970s: oil price shocks caused by OPEC and the Iranian revolution followed President Nixon's decision to exit from the Bretton Woods agreement and to devalue the dollar. This was a decision forced by inflationary policy priorities in the US and several other Western nations.

- Late 80s: The 'Lawson Boom' in the late 1980s eventually forced the UK Treasury to hike interest rates sharply, prompting a recession and a deeply unpopular adjustment to house prices. It has come to be associated with deregulation of financial markets in the City of London, the so-called 'Big Bang', but is recognised by economists to be a result of political reluctance to raise the bank rate of interest.

- 2022: Energy costs in Europe were rising substantially in advance of the Ukraine war, due to a range of political and economic inputs. The gas shortage in Europe following Russia's invasion of Ukraine only amplified an existing inflationary trend as the global economy re-opened following pandemic lockdown.

How do central banks manage inflation?

Central banks hold two big levers to manage inflation – setting central bank interest rates, and changing the quantity of money in circulation. They use both tools to influence lending rates on offer in the market.

When they raise interest rates to control inflation, central banks aim for a 'soft landing' – slowing the rate of economic growth but avoiding a recession (a 'hard landing').

A central bank will usually share its analysis, projections and decision-making as transparently as possible, to minimise surprises and market volatility. This can grant businesses and consumers time to adapt and plan.

1. Setting the bank rate

In the UK, the bank rate is the interest the Bank of England will pay to commercial banks depositing their money with the Bank. The bank rate influences interest rates in the retail market; for businesses, homeowners and consumers.

Lowering the rate of interest stimulates economic activity by encouraging borrowing and making investing relatively more attractive than saving. This can have the side effect of raising inflationary pressures.

Raising interest rates has the opposite effect – discouraging borrowing, damping economic activity, reducing consumption and raising the likelihood consumers place their money into savings to earn interest.

2. Changing the supply of money

Quantitative easing (QE) means that the central bank buys bonds (in the UK this is mainly UK government bonds, known as gilts) from the investors who hold them. This raises the market price of bonds, reducing their long-term interest rate.

The reduction in interest rate occurs because the fixed interest payable on the bond is now calculated as a percentage of a higher bond price.

This technique aims to avoid directly flooding the economy with 'new money' by keeping it mainly on central banks' own balance sheets - because the central bank is buying back long-term bonds it has already issued. This may support banks' solvency – and so their ability to supply credit to the economy.

The Bank of England first began using QE in March 2009 in response to the global financial crisis. At that time bank rate was already very low. In fact, it couldn’t be lowered any further at that point. So, policy makers needed another way to encourage spending in the economy, and meet the Bank's inflation target.

By lowering interest on bonds and stimulating borrowing, quantitative easing can indirectly increase inflation. Markets expect central banks to ‘unwind’ these positions and sell bonds back into the market when inflation is high – ’quantitative tightening’.

UK interest rates in context

For most of the 20th century, the UK bank rate floated in a range of 5-10%. Rates reached 17% when the incoming Conservative government in 1980 took emergency measures to control inflation. They remained high throughout the following decade, and spiked again at 15% in 1990.

The Government delegated setting the bank rate to the Bank of England and its Monetary Policy Committee in 1998, and interest rates subsequently hovered around 5%. However, they were brought down to nearly zero for the decade following the global financial crisis in 2008, and were raised up again sharply to around 5% as inflation spiked, post-Covid pandemic.

How do rate changes affect consumers, businesses, and markets?

When interest rates go up, it costs consumers more to borrow money from the bank (loans, credit cards, mortgages), and so they are likely to spend less. Meanwhile, if they keep this money in a savings account, they are in effect lending to a bank and benefit from these high rates. However, note that interest rates offered by banks are not always linked to base interest rates; they are likely to be lower.

Businesses also face higher costs of borrowing when bank rates are high. When coupled with a drop in consumption, they become less willing to spend money on expansion and productivity. This can have a downward impact on share prices for listed companies.

This means that high interest rates have historically - though not always - slowed equity market growth.

When a central bank, such as the Bank of England, lowers interest rates, this also means the interest rates on savings accounts becomes less rewarding than the potential returns of investing. Meanwhile, it becomes cheaper for individuals and businesses to borrow and spend, which can contribute to economic growth. Under these conditions, investors may find that this increased economic activity also means it may be logical to be positioned to benefit from opportunities in equities at that point in the cycle.

In terms of fixed income or bonds, investments can see their returns undermined by unexpected inflation. Typically, expected inflation will already be factored into the fixed rate of return demanded by bond markets. If the policy interest rate is unexpectedly changed, then bond prices will be affected. Higher rates tend to weaken bonds and visa versa.

Bonds have an inverse relationship with interest rates in that when rates go up, the price of most existing bonds will tend to fall, and vice versa when rates go down.

How Nutmeg manages portfolios as rates rise or fall

As part of ongoing macroeconomic and market analysis, the Nutmeg investment team work to anticipate and mitigate risk and harness the long-term opportunities that changing inflation and interest rates may bring.

They do this by observing a wide range of trends across the global economy, for example, analysing the yield curve on bonds for indicators of a change in market sentiment.

The team can change the allocation of Nutmeg portfolios, across different equity markets and types of fixed income - both corporate and government bonds - dependent upon economic conditions. How this works in practice is dependent on your chosen investment style and risk level.

What can I do to make the most of interest rate and inflation conditions?

1. Get the best rates. Consider a balance of saving and investing: save in a high interest account for short-medium term goals, invest for long-term goals.

2. Diversify. By spreading your investments across a balanced portfolio of assets - such as those offered by Nutmeg - you can potentially minimise the impact of interest and inflation rate changes and improve your chances of steady returns.

3. Don't try to play the market. Pick an investment strategy and an appropriate risk level and let our expert team take care of the regular trading decisions.

4. Contribute. Determine your goals and set an investment plan with a time horizon of at least five years – and stick to it. Maximising regular contributions can have a big impact on returns through compounding.

5. Ask an expert. Our experts can answer your questions in a free call, or if you prefer, just pay a flat fee for a personalised investing plan tailored for you.

How Nutmeg can help

We hope you've found this guide helpful.

Need more information about different investments? Book a free call with an expert from our team to discuss your options.

Our team can help you to get a clear view on different ISA and pension wrappers, as well as our investment styles. We can review your current strategy, and help you to make the most of your allowances. Get ahead with free financial guidance to set yourself up for success.

Risk warning

As with all investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Nutmeg can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Tax treatment depends on your individual circumstances and may be subject to change.

Nutmeg provides restricted advice. This means our advice is limited to our own products and services.